http://www.bigredhair.com/frankreade/family.html

This has a lot of details of the Reade family stories and their inventions, primarily airships but also steam-powered robots. There is also information on there about Edward S. Ellis who wrote about a steam-powered robot in 'Steam Man of the Prairies' (1865). It is quite difficult to tease out what is real and what is made-up history, for example in the case of the Boilerplate robot produced by Professor Archibald Campion in 1893.

Another excellent resource is the Fantastic Victoriana website which has a dictionary of a wide range of characters from Victorian novels, focusing on heroic, criminal and inventor characters. This is the electronic version of a book apparently published in 2005. The entries about each character are very detailed and cross-referenced. It is a really good resource if you want to slip in reference to characters from the time in your steampunk stories or your version of 'The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen': http://www.geocities.com/jessnevins/vicintro.html

Sorry, back to the Reades. As has been identified, 'The Eclipse' that I stumbled across, is a Reade airship as were the Cloud-Cutter, the Flight, the Catamaran of the Air and the Thunderer. The Reades also built jet packs, helicopters tanks, spaceships, submarines and vehicles which could change form. The stories ran from 1876 and covered the exploits of Frank Reade, Frank Reade Jr., Frank Reade III (they are Americans) and Kate Reade (Frank Reade III's sister) who disappeared in 1944, ending the series. The authors varied, beginning with a Harold Cohen (1854-1927), then Luis Senarens (1863-1939) who started writing the stories at the age of 16.

It has been claimed that Senarens was in correspondence with Jules Verne and they each copied the other's ideas in various ones of their stories, with Verne using Senarens's ideas in 'The Steam House' (1880) which features a steam-powered elephant robot. It is said Senarens used the model of Verne's 'Albatross', the helicopter-airship of 'Robur the Conqueror, or the Clipper of the Clouds' in his own 'Frank Reade, Jr., and His Queen Clipper of the Clouds' (1889). It is claimed Verne borrowed a Reade vehicle for 'Master of the World' and so on. However, as Ron Miller pointed out to me (see his comment below), this appears rather to be modern commentators distorting history. He notes Verne (1828-1905) did not read English well, making correspondence between the two men very difficult and Verne's work was well developed even before Senarens was publishing. Miller also notes that in 1862, before Senarens's birth, Verne had been involved in a group to develop heavier-than-air helicopter style craft and he featured designs by inventors in his circle in his novels. It seems clear that there is a process of American cultural imperialism going on currently to suggest that steampunk stems largely from US roots. Correcting this impression does not diminish what Senarens did, but it allows Verne's reputation as a true innovator to remain unsullied.

These stories are very much in the genre of the Thomas Swift stories that followed through the twentieth century which I have previously mentioned. Jess Nevins on 'Fantastic Victoriana' terms such stories Edisonades, i.e. stemming from the kind of inventive behaviour of Thomas Edison. Many critics point to the racist approach of the stories, in that all the opponents of the young inventor heroes, are non-Whites. However, this charge can be laid at much literature of whatever genre the 19th century. As Nevins notes, such racist characters can be found in the works of Verne and Wells, but science fiction writers of the time were not unique in that. When you had the Kaiser of Germany referring to the 'Yellow peril' of the Chinese and racist legislation not only in the USA but other states, as well, it is unsurprising to find such attitudes, just as we see anti-asylum seeker attitudes in some work today.

The Reades, even more than Verne's characters, are certainly not pirates. As in modern movie making, it is interesting to see that the US audience was not even willing to tolerate the moral ambivalence that we find in Verne's characters. To some degree, though, this is because the Reade stories were produced in weekly magazines for boys, whereas Verne was producing novels for adults. Anyway, for steampunks today, there is a lot to mine from the Reade stories. It would be nice if someone could produce one in which the outdated attitudes of the 19th century were turned on their head, and say, an African-American inventor (or an Afro-German one, as noted before Germany's black population of the 19th century gets very overlooked) uses an airship to release Congolese from repression by the Belgians in the 1880s or Hereros or Himbas to escape from the German genocide in what is now Namibia in the 1900s.

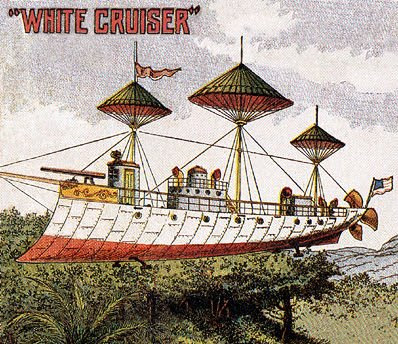

Anyway, to round off this section, another nice picture of a Reade airship, ironically known as the 'White Cruiser', clearly a flying ironclad:

The other writer MCG recommended was George Griffith (1857-1906). By now I was feeling that I must hang my head in shame for not having heard of him before. I did realise that I had read a story by him probably 25 years ago in Michael Moorcock's collections of imaginary fiction from the later 19th/early 20th century: 'Before Armageddon: An Anthology of Victorian and Edwardian Imaginative Fiction Published Before 1914' (1975). In that collection is his story, 'The Raid of Le Vengeur' (1901). I highly recommend reading this anthology and its sequel 'England Invaded' (1977).

Griffith bisects with another area of interest of mine, which is pre-1914 invasion fiction, stories warning about the invasion of Britain by one or other of its European rivals (for comprehensive analysis of such fiction see 'Voices Prophesying War: Future Wars 1763-3749' by I.F. Clarke(1993)). He also wrote what we would now see as classic science fiction with stories of people travelling the solar system and beyond, sometimes as tourists, and also wearing spacesuits. Given he died almost fifty years before this happened, he was very prescient. See 'A Honeymoon in Space' at: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/19476

Unlike many such authors Griffith lived an adventurous life, circling the World in 65 days and discovering the source of the River Amazon. A number of his stories, such as 'The Romance of Golden Star' (1891) and 'The Virgin of the Sun: A Tale of the Conquest of Peru' (1898) are set in South America.

Griffith's best known novel was 'The Angel of the Revolution: A Tale of Coming Terror' (1893) which is set in 1903 and features Russian revolutionaries who create aircraft to challenge the Tsarist system by using aerial bombing (sound familiar?). This shows Griffith's political awareness because in 1905 Russia experienced its first revolution, of course followed by two more in 1917, the first of which overthrew the Tsar. Interestingly, given what was said above about racism in Edisonades, the heroine of the novel, Natasha, the 'angel' of the story, is actually a Jew. In some ways, Griffith is like Wells in being aware of the contemporary context in which his fantasies were being created. For example, 'The Stolen Submarine: A Tale of the Japanese War (1904)' was published at the time of the Russo-Japanese War.

'The Angel of the Revolution' is online at: http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0602281h.html ; http://www.pagebypagebooks.com/George_Chetwynd_Griffith/The_Angel_Of_The_Revolution/ and at: http://forgottenfutures.com/game/ff7/angel.htm so there is no excuse not to read it.

There was a sequel called 'The Syren of the Skies' or 'Olga Romanoff' (1894). It can be found at: http://forgottenfutures.com/game/ff7/olga.htm

Despite the title 'The Outlaws of the Air' (1895) we do not find steampunk pirates, rather more attempts to build a utopian island in the Pacific. This is reminiscent of Aldous Huxley's 'Island' (1962) though with aircraft, including one called the 'Nautilus' featured. You can read this at: http://www.forgottenfutures.com/game/ff9/outlaw.htm Again, we have heroes who want to move to a more peaceful world through the deterrent of airpower rather than raiding as pirates. Perhaps these two things are forever linked.

Other novels by Griffith I cannot find out so much about but you can read his 'The World Peril of 1910' (1907) at: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/24764 and the wonderfully titled, 'The Mummy and Miss Nitocris: A Phantasy of the Fourth Dimension' (1906) at: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/19231

The author Michael Moorcock, who I ran into in Oxford back in the mid-1990s when cycling, was very influenced by Griffith and weirdly you find that David Bowie produced an album in 1974 which was set in a post-apocalyptic world and was called 'Diamond Dogs'. In interviews I have also heard that he was influenced by the Gormenghast triology of Mervin Peake as well as George Orwell's 'Nineteen Eighty-Four'. However, I do not know if he or someone working on the album was also aware of George Griffith's novel 'The Diamond Dog' published in 1913, seven years after his death.

My quest for steampunk pirates has not really turned up many examples, but for me it has uncovered a lot of literature which not only forms the bedrock of steampunk, but also raises questions about the appropriate approaches and attitudes of technology-focused fiction.

I wish there were some basis for the old wive's tale about Senarens and Verne corresponding...but there is really not one shred of evidence (other than Senarens' own claim) that this ever occurred. In addition to the lack of any surviving letters is the fact that Verne could barely---if at all---read English. But even more damning is the timing. The claim that Verne was "inspired" by Senarens' flying machine stories to write "Robur the Conqueror" collapses immediately when one looks at the chronology. Aside from the fact that "Robur" was published first, Verne had been intimately involved with heavier-than-air flight, and specifically helicopteral flight---before Senarens had even been born! Verne was one of the founding members of an aviation society launched in France in 1862 that was dedicated to building and flying some type of helicopter. The designs of several of the society's members---such as Cossus, de la Landelle, Nadar and d'Amecourt, closely resembled the "Albatross" in "Robur"...de la Landelle's machine most specifically so. Verne credited these and other early heavier-than-air aviation pioneers in the book. It is perfectly obvious that Verne got nothing from Senarens and that if any copying was going on it was one-way in the direction of America.

ReplyDeleteRon, yes, reflecting on this, I think you are right. I will amend my posting accordingly. I suspect this is simply a case of the Americans trying to steal some of the thunder from Verne's work. I know Michael Moorcock was an editor at 16, but it seems unlikely Senarens was working at this level, despite the claims that I have read and what seems to be the established wisdom. I know from my own experiences that people can come up with similar ideas at the same time. This now just appears to be US cultural imperialism at work even 120+ years after the event.

ReplyDelete